Red Hook Initiative WiFi is a collaboratively designed mesh network. It provides Internet access to the Red Hook section of Brooklyn, NY, and serves as a platform for developing local applications and services. Red Hook Initiative has built the network in partnership with the Open Technology Institute, putting human-centered design and community engagement at the core of the project.

The community expanded the network significantly following a natural disaster in the Fall of 2012.

- Main network anchors are trusted community organizations.

- Solid relationship with technical support provider from outside the community.

- Solid relationship with technical support provider from outside the community.

- Rapid prototyping of applications designed for the local area network.

Beginning in Fall 2011, the Red Hook Initiative (RHI), a Brooklyn non-profit focused on creating social change through youth engagement, approached the Open Technology Institute about collaborating on a community wireless network. RHI wanted a way to communicate with the residents immediately around its community center. OTI was initially unable to support the effort directly, but introduced Anthony Schloss, RHI Media Programs Coordinator, to Jonathan Baldwin, a Parsons School of Design graduate student who had been experimenting with wireless mesh as a local digital platform.

Figure CsOTI 1: Red Hook West Houses - public housing buildings

Figure CsOTI 1: Red Hook West Houses - public housing buildings

Red Hook is the northwestern corner of Brooklyn, jutting out into the Hudson Bay. It is cut off from the rest of the borough by the Gowanus Expressway, which carries traffic from points south into lower Manhattan.

The neighborhood is home to approximately 5000 residents of Red Hook Houses public housing and other low income areas near an expressway, as well as a gentrifying section with many small businesses closer to the water. Many industrial sites, an Ikea and a number of public parks fill out the area.

Figure CsOTI 2: Walking from RHI Offices to Gowanus Expressway

Figure CsOTI 2: Walking from RHI Offices to Gowanus Expressway

Figure CsOTI 3: Gowanus Expressway which divides the Red Hook neighborhood from the rest of Brooklyn.

Figure CsOTI 3: Gowanus Expressway which divides the Red Hook neighborhood from the rest of Brooklyn.

RHI WiFi’s initial plan was to provide wireless access to the Internet in and around RHI’s building, which is near the expressway and the Red Hook Houses. Schloss and Baldwin installed a Ubiquiti Nanostation on the roof and a Linksys router inside the building, connected via ethernet.

They connected the Linksys router to the center’s modem. This installation provided an opportunity to prototype early versions of RHI WiFi local applications. When residents or visitors to RHI connected to the wireless access point named “Red Hook Initiative WiFi,”they were directed to a website on a local server. On this website was a “Shout Box,” a local digital message board allowing everyone to leave a comment or a note behind and participate in the project.

Figure CsOTI 4: First RHI WiFi node (Ubiquiti Nanostation) installed on the rooftop of the building that houses the RHI offices.

Figure CsOTI 4: First RHI WiFi node (Ubiquiti Nanostation) installed on the rooftop of the building that houses the RHI offices.

In March of 2012, Baldwin and Schloss installed an additional Ubiquiti Nanostation on the roof of an apartment building overlooking Coffey Park and much of the rest of the neighborhood. A resident of the building with social ties to RHI donated the electricity and rooftop access.

With this vantage point on the neighborhood, the possibility of a wireless network connecting public spaces began to take shape. Initially, the Coffey Park wireless access point was not connected to the Internet, but was connected to a GuruPlug Server.

The basic, low power server hosted a local web page on the network and a “Shout Box” similar to the one running in RHI.

Figure CsOTI 5: Running cable to install a node on the roof of an apartment building north of Coffey Park.

Figure CsOTI 5: Running cable to install a node on the roof of an apartment building north of Coffey Park.

Figure CsOTI 6: Node installed on the roof of an apartment building.

Figure CsOTI 6: Node installed on the roof of an apartment building.

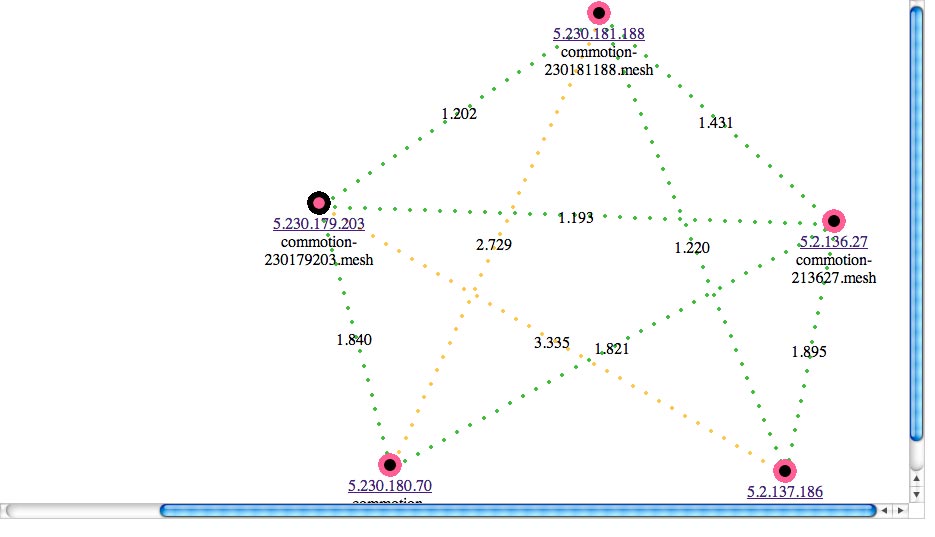

RHI WiFi uses OTI’s Commotion Wireless firmware running on Ubiquiti routers. Commotion is a free and open-source communication tool that uses mobile phones, computers, and other wireless devices to create decentralized mesh networks.

Most importantly, Commotion allows network development to occur dynamically and organically - so the community can decide where and how the network should grow.

Commotion networks are sustainable without a connection to the Internet, which makes them resilient to outages; they can distribute access to applications hosted on local servers or on the routers themselves.

Based on research into community wireless networks around the world, Baldwin had identified a need for social software that would add value and a distinct identity to the community wireless network, specifically to:

- Spark civic and community engagement by addressing local needs, interests and culture.

- Foster trust, interdependence, and reciprocity throughout the community.

- Merge digital and physical community spaces.

- Ensure that people know about mesh / have software installed before a communication outage occurs.

Schloss and Baldwin began working with participants in RHI’s established media programs on a collaborative, human-centered design process that called upon the knowledge and interests of local residents.

Throughout the first year, Baldwin and Schloss held workshops with community members to determine local needs and gather design ideas for Tidepools, developed by Baldwin for piloting on the RHI network. Tidepools is an open-source customizable local mapping platform built using Javascript, LeafletJS, PHP and MongoDB.

Baldwin designed it for local communication, placemaking, and organizing around events, issues, and community assets.

Figure CsOTI 7: Workshop to identify local needs for RHI WiFi network. (Photo by Becky Kazansky).

Figure CsOTI 7: Workshop to identify local needs for RHI WiFi network. (Photo by Becky Kazansky).

Figure CsOTI 8: Tidepools map of RHI WiFi network.

Figure CsOTI 8: Tidepools map of RHI WiFi network.

Schloss and Baldwin began working with participants in RHI’s established media programs on a collaborative, human-centered design process that called upon the knowledge and interests of local residents.

The community workshops produced ideas for local applications that would address specific needs identified by the community.

The needs identified in the community workshops were:

- Access to the Internet (at home, via mobile, and at neighborhood kiosks).

- Accountable community participation (FAQs, electronic bulletin boards, SMS enabled features).

- Access to resources (employment and skills sharing).

- Local Information System (historical archive, landmarks).

- Multilingual (Spanish, Arabic and Tagalog).

- Playful interface to promote exploration.

In the summer of 2012, Baldwin joined OTI’s staff, and OTI brought additional tech expertise to the collaboration along with experience closing digital divides and developing community-controlled infrastructure.

The organization’s experience in Detroit and Philadelphia provided guidance on how to collaborate with communities that have been socially, geographically and technologically isolated within cities.

During the months following the initial tests of the local network, OTI and RHI focused on realizing three initial applications that would use the Tidepools platform and run over the local wireless network:

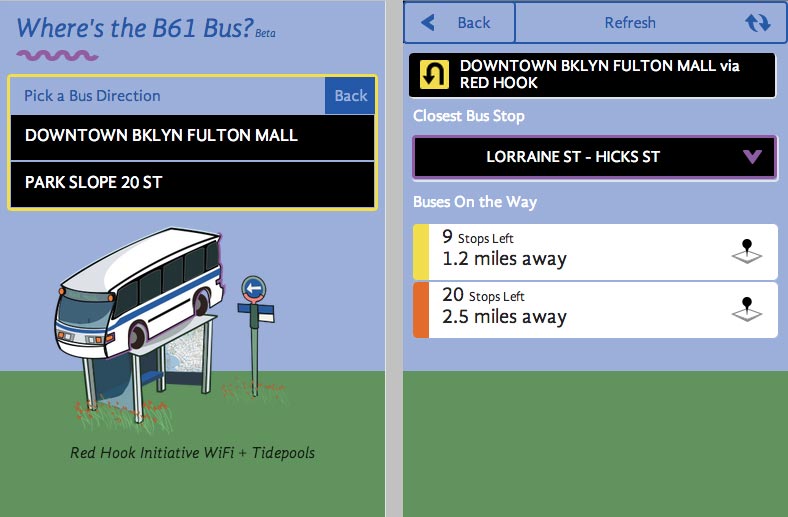

- Where’s the B61 Bus? - An application for accessing real-time bus locations and arrival times using data from the Metropolitan Transit Authority’s BusTime API (launched October 9, 2012).

- Stop & Frisk Survey - A survey application that residents can use to document police interactions in Red Hook and improve public safety (launched October 17, 2012).

- RHI Radio - An online radio station, streaming content produced by the Youth Radio Group at RHI (under development).

Figure CsOTI 9: Magnet advertising "Where's the B61 Bus". Tidepools application.

Figure CsOTI 9: Magnet advertising "Where's the B61 Bus". Tidepools application.

Figure CsOTI 10-11: Mobile user interface for "Where's the B61 Bus?" application.

Figure CsOTI 10-11: Mobile user interface for "Where's the B61 Bus?" application.

On October 29, 2012, Superstorm Sandy devastated low-lying Red Hook along with much of the surrounding region. Amid power outages and flooding, the need for access to communications systems for information about what was happening and where help was needed became crucial.

The RHI building was one of the few locations that had managed to keep power and, as a result, RHI WiFi had stayed up through the storm. In the days immediately following the storm, up to 300 people per day were accessing the network to communicate with loved ones, learn what was happening in the rest of the city, and seek recovery assistance.

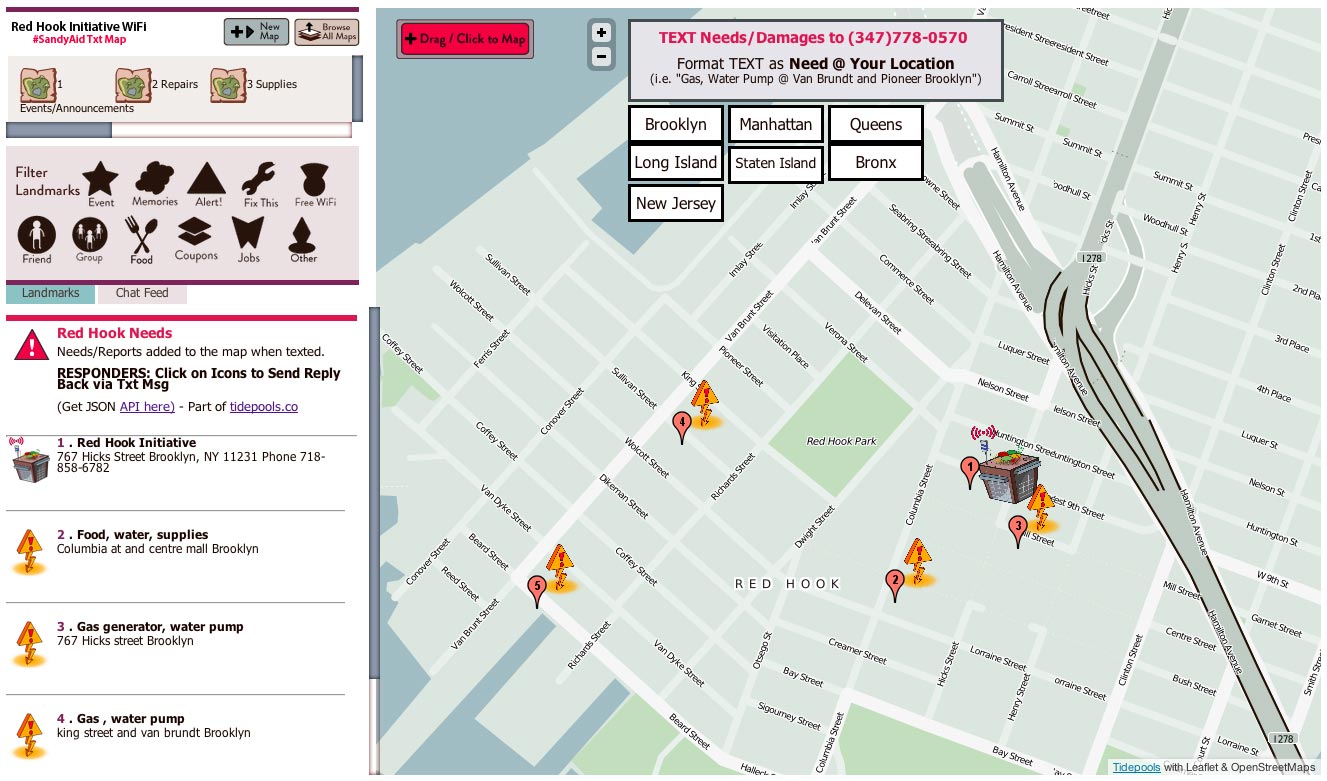

Text messaging was the most widely – and in some cases the only – means of communication for neighborhood residents after the storm, so in a matter of days, OTI developed RHI Status - an SMS to Map plugin for Tidepools using the Tropo Application Programming Interface (API) for handling SMS messages and the Google Geocoding API for handling natural language addresses.

RHI Status provided a means for residents to text their location and needs to a contact number, which automatically maps the information in Tidepools with threaded discussion so others in the community can respond.

Figure CsOTI 12: Screenshot of RHI/Status application, which plots SMS messages on a Tidepools map.

Figure CsOTI 12: Screenshot of RHI/Status application, which plots SMS messages on a Tidepools map.

As recovery progressed, Frank Sanborn, a Federal Emergency Management Administration (FEMA) Innovation Fellow, reached out to RHI about expanding the network to further support recovery efforts in Red Hook. Sanborn recruited volunteers from NYC Mesh and HacDC, a Washington, DC based hackerspace, and coordinated with the International Technology Disaster Resource Center (ITDRC).

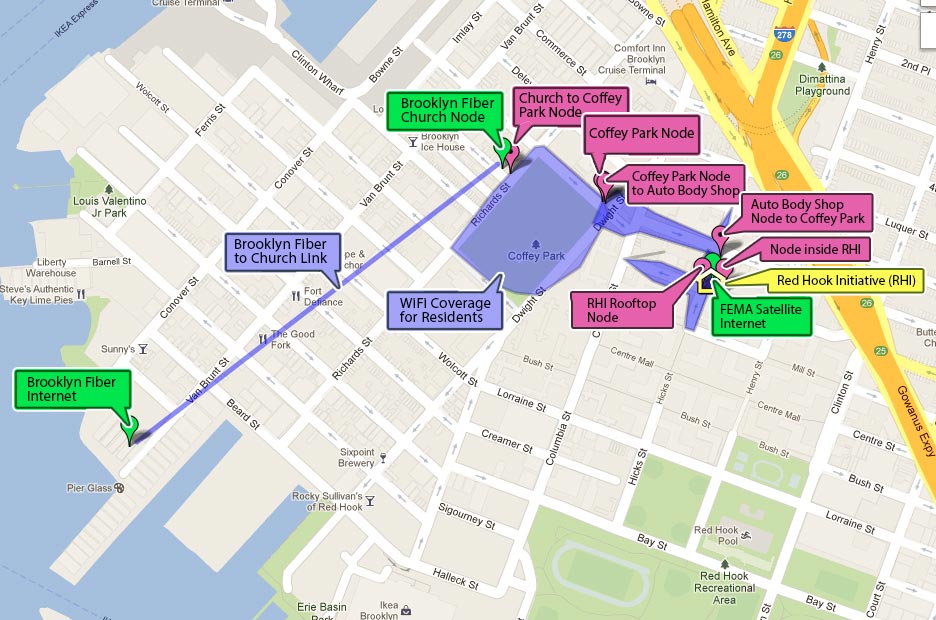

OTI already had a store of routers at RHI from before the storm. With technical direction from OTI and operating according to the goals established by RHI, the team set up a FEMA satellite link on the roof of RHI and installed a Commotion router on the roof of an auto body shop down the block from RHI. Previously, the owner of the shop had been reluctant to host a router, as he did not see a benefit in doing so. However, as the community rallied in response to the crisis, the auto body shop became a key link between the Internet gateway at RHI and the router overlooking Coffey Park, which had by then become an important aid distribution point for Red Hook.

Although the satellite uplink was offered for only 30 days and provided modest bandwidth, the mesh network could distribute the Internet connection to key locations where residents, first responders, and recovery volunteers needed it most.

As the community came together to respond to the storm, the need to grow this resilient communications infrastructure became clear. With power and water still off in much of Red Hook in the following month, many local organizations and residents reached out to help. Brooklyn Fiber, a local Internet service provider (ISP), volunteered an additional gateway to RHI WiFi.

To add the gateway into the mesh, OTI, RHI and Brooklyn Fiber installed a 5 GHz Ubiquiti Nanostation Loco router running AirOS (to receive the fiber signal), and a Ubiquiti Nanostation running Commotion (as a wireless access point), on the 3rd floor of the Visitation Church Rectory on the west side of Coffey Park. The church was also without power at the time, but the team installed an uninterruptible power supply that could run the routers for 12 hours at a time.

Figure CsOTI 13: Rooftop node. In the aftermath of Superstorm Sandy, additional community members offered to host RHI WiFi nodes and a local ISP donated Internet connectivity.

Figure CsOTI 13: Rooftop node. In the aftermath of Superstorm Sandy, additional community members offered to host RHI WiFi nodes and a local ISP donated Internet connectivity.

Figure CsOTI 14: Rooftop node installed after Superstorm Sandy.

Figure CsOTI 14: Rooftop node installed after Superstorm Sandy.

Since the storm, RHI WiFi has supported approximately 100 users per week even without promotion of the resource.

Data collected by Commotion on current DHCP leases, as well as the Google Analytics on the landing webpage, show that residents appear to be primarily connecting using Android devices and Apple iPod Touches.

In addition, many residents use the computer workstations in the RHI media lab as well as the wireless available in RHI. RHI is serving as both a physical and social anchor for the wireless network, driving digital adoption, educating the neighborhood, and coordinating relief efforts.

Figure CsOTI 15: RHI WiFi network map. Base map (c) Google Maps 2013.

Figure CsOTI 15: RHI WiFi network map. Base map (c) Google Maps 2013.

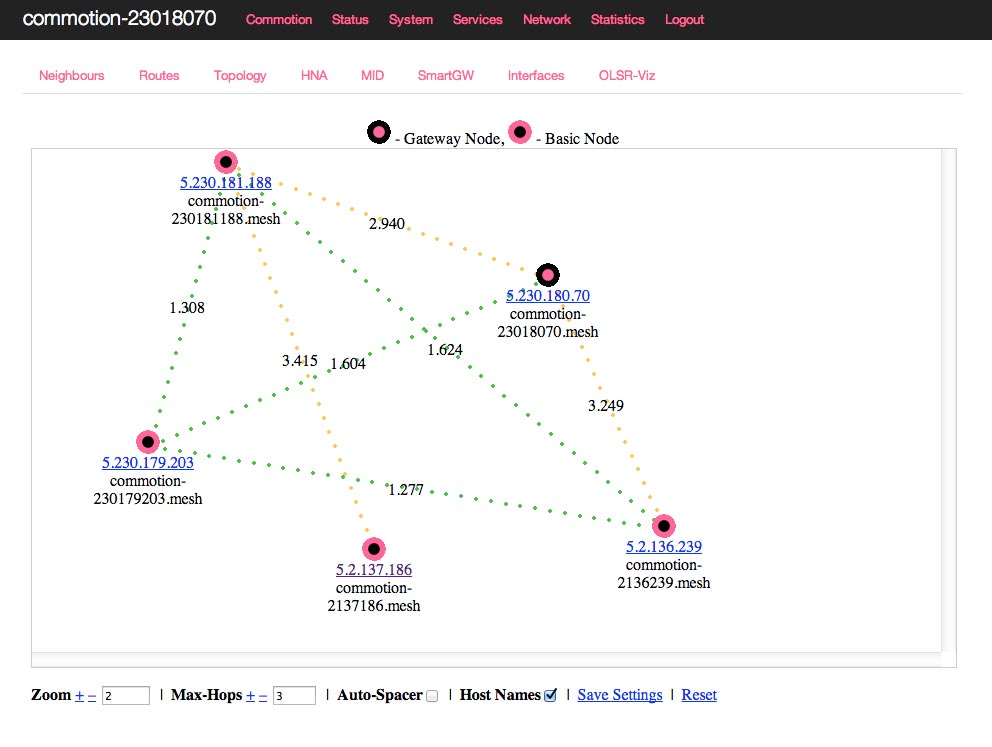

Figure CsOTI 16: Mesh network topology viewed in OLSRViz.

Figure CsOTI 16: Mesh network topology viewed in OLSRViz.

Figure CsOTI 17: Mesh network topology viewed in OLSRViz.

Figure CsOTI 17: Mesh network topology viewed in OLSRViz.

RHI will continue to develop the project with the goal of supporting community-wide recovery from Superstorm Sandy. With support from New York City Workforce Development funding, RHI and OTI are launching a training program in January 2013 to engage neighborhood residents in maintaining and growing the wireless network. Modeled on the “Digital Stewards” curriculum developed by OTI and Allied Media Projects in Detroit, Michigan, the curriculum will train young adults to install new routers, maintain existing ones, and promote adoption of the RHI WiFi network throughout Red Hook. The RHI Digital Stewards will prioritize additional public spaces for network expansion and work with other residents to design new, local applications. OTI will continue to assist in the development of the applications and support the engineering of the network in close collaboration with the community.

Donated labor from local residents and technologist. Institutional support from RHI and OTI. Hardware (~$50 to ~$85 each router).

Installation (3-5 work hours for two people per site). Bandwidth (donated by RHI, Brooklyn Fiber, and FEMA). Training program for local residents to maintain and expand network as part of a municipal employment program.

Having relationships and anchor wireless nodes in place prior to a disaster facilitates rapid network deployment through:

- Already-established relationships with key community stakeholders.

- A heightened level of technological literacy in the community.

- Pre-positioned wireless network equipment in the neighborhood.

The most challenging investment is in the initial organizing and design phase before any value is realized. Community-designed applications add value to a local network, even at a small scale.

New Community-Tech Tool to Help in Sandy's Aftermath - oti.newamerica.net/pressroom/2012/release_new_community_tech_tool_to_help_in_sandys_aftermath

What Sandy Has Taught Us About Technology, Relief and Resilience - www.forbes.com/sites/deannazandt/2012/11/10/what-sandy-has-taught-us-about-technology-relief-and-resilience

A Community Wireless Mesh Prototype in Detroit, MI - www.newamerica.net/node/34925

Tidepools - tidepools.co

www.animalnewyork.com/2012/tidepools-a-social-networktool-in-the-service-of-the-community

wlan-si.net/en/blog/2012/05/26/introducing-tidepools-social-wifi

www.core77.com/blog/social_design/a_community-owned_map_accessed_via_mesh_networks_23319.asp

www.jrbaldwin.com/tidepoolswifi

Stop & Frisk App animalnewyork.com/2012/stop-and-frisk-app-launched-by-red-hook-initiative www.dnainfo.com/new-york/20121017/red-hook/stop-and-frisk-app-launched-by-red-hook-initiative

Red Hook www.nycgovparks.org/parks/redhookpark/history